- Written:

- Author: Edward

- Posted in: dr ed park, existentialism, love, philosophy

- Tags: anxiety, attending, Dr. Ed Park, flow state, nightmares, parenting, residency, surgery, teaching hospital

Fractally speaking, they say that how you do one thing is how you do everything. It seems a bit simplistic but like golf, my dream this morning revealed that surgery is a good metaphor for life.

Owing to some challenges I face in guiding my teenage sons, my subconscious and the vivid adaptogen-fueled dreams conspired to treat me to quite the anxiety dream!

In my dream, I was assisting a surgery, a vaginal hysterectomy to be precise, when the surgeon decided to finish off the procedure by simply pulling out out the uterus! There was no blood but in my judgement, the proper procedures of ligating off the vessels and properly closing the patient were neglected and this might lead to post-operative disaster.

The surgeon and the staff called it quits but I declined. So I had to cajole the anesthesiologist to keep the now waking patient asleep. I had to find my own instruments that I would need, and I repositioned the patient, running through the steps I would need to take in my mind as everyone abandoned the operating room.

For those of you who have never operated, let me share some insights. When you are a resident in training, you are like an orphan going from family to family and seeing how they conduct themselves. Each surgeon has their own techniques, tendencies, responses to stress, and idiosyncrasies. Within reason, as a resident, you are not expected to contradict the poor judgement or surgical technique of your attendings, who are like your parents.

As such, you get to learn a lot of ways to do things and develop your own approaches. If you are wise, you learn quickly from other people’s mistakes; if you are clever, you humbly display a better technique after gaining trust and let the deficient “teacher/parent” learn from you.

Years later, in a private community hospital OR, I was assisting a surgeon once who used some horrifying techniques and when I asked why he did something, he proudly said, “I have been doing it this way for twenty years!”. I thought to myself, “you’ve been doing it wrong and must have caused a lot of problems that were avoidable.” Kind of reminds me of cohorts in the latchkey Gen-X who grew up with corporal punishment, second hand smoke, and no seat belts when we ending absurd sentences with “…and I think we turned out just fine!”

Therein lies the beauty of being in a teaching hospital environment. With any luck, everyone is cross-pollenating and continuously learning instead of being an island unto themselves. As with any human endeavor, the more respected and isolated you become, the fewer people are available to teach and correct you.

Today, a very kind patient reminded me that the purpose of being my own “attending” parent to my “resident” children, was not only to guide and teach, but also to be guided and taught. She said to always “come from a place of love” rather than a place of fear of them making mistakes.

I told my son today that the greatest problems in surgery (as in life) come from two things: laziness and fear. Surgeons who take shortcuts and make assumptions are dangerous. Oddly, you might think as a patient that a “cowboy” is the person you would want operating and indeed there can be some who are overly reckless. But in my experience, most surgical complications come from operators who are afraid of something and therefore don’t take the necessary steps to do the things that are hard- even if that means asking for help.

One of my memories from residency was helping a patient that many others had previously passed on helping. She was a Jehovah’s Witness (meaning she wouldn’t accept blood and would rather die). Secondly, she was HIV positive. She came to me with a massive uterus filled with fibroids that was causing her heavy bleeding, pain, and anemia every month.

Looking back, some people might have thought I was crazy, altruistic, reckless, or dumb. I suppose the ability to see the case as a calculated risk is a bit unusual and yes, I would have let her bleed to death since that was her wish but I deemed the risk low.

That potential nightmare of a case was uneventful for all and her blood loss was minimal. No one contracted HIV and her problem was resolved.

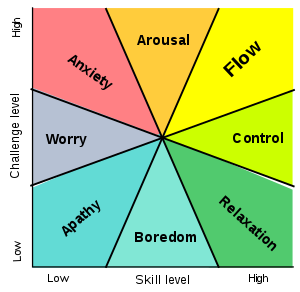

Performing surgery requires knowledge, dexterity, patience, judgment, bravado, and humility. But honestly, you can train a monkey (or a robot) to do it technically well. In the larger scheme of things, being a good surgeon means being a good person. You have to always keep your patient’s best interests in mind, even if you might be late for a tee time or an office full of patients. To do a difficult  thing well is to be in what Mihaly Csikszentmihaly called a “flow state” and there is a certain pleasure from operating. But the real gratification, like all virtue, is that no one will ever appreciate just how brave you were when you did what you did, in the right way, for the right reasons, with the best possible results. Maybe being an effective parent is a little like that. Thankless, hidden, and yet satisfying when you know you left little to chance and gave it your best effort.

thing well is to be in what Mihaly Csikszentmihaly called a “flow state” and there is a certain pleasure from operating. But the real gratification, like all virtue, is that no one will ever appreciate just how brave you were when you did what you did, in the right way, for the right reasons, with the best possible results. Maybe being an effective parent is a little like that. Thankless, hidden, and yet satisfying when you know you left little to chance and gave it your best effort.

If you want to learn more about flow states and human consciousness, read my book, The Telomere Miracle.