- Written:

- Author: Edward

- Posted in: dr ed park, Telomere erosion

- Tags: bristlecone pine, Dr. Ed Park, flanary, immortality, lobster, longevity, telomerase, telomere

In a fascinating article, researchers looked at telomeres and telomerase activity from the needles, core, and roots of six tree species with an  emphasis on the Bristlecone Pine, known to live nearly 5,000 years, which makes them older than the Great Pyramid of Giza.

emphasis on the Bristlecone Pine, known to live nearly 5,000 years, which makes them older than the Great Pyramid of Giza.

[Flanary BE, Kletetschka G. Analysis of telomere length and telomerase activity in tree species of various life-spans, and with age in the bristlecone pine Pinus longaeva. Biogerontology. 2005 March; Volume 6, Issue 2, pp 101-111 ]

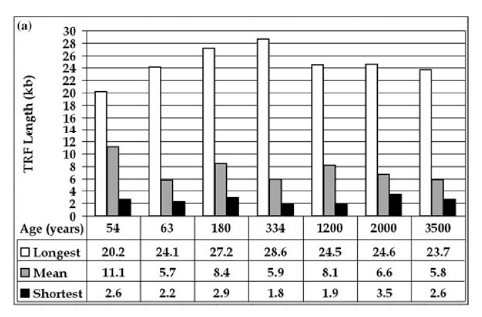

There was a tendency for the longer telomeres and the higher activity to be associated with longer lifespans but the relationship was far from linear.

Actually, the most interesting thing was that the authors concluded that over the course of thousands of years, the telomeres of the ideal species waxed and waned but they never became “Rapunzeled” and too long nor did they become too short as always occurs in conjunction with our own relatively meager lifespans. To quote Goldilocks, telomeres of trees stayed “Juuuust right.”

This chart shows the longest, average, and shortest telomeres from the needles of the tree at various ages from 37, to 334, to 3500.

Unfortunately, the authors suffered from a certain logical misstep. They used a snapshot of individual trees of varying ages to generalize about the cyclicity of telomere length in the species. That would be like taking a snapshot of humans at various ages and telomere lengths and expecting it tell you anything about one ideal human. I explain in this video presentation to a Biomarkers Conference why that doesn’t work.

Who is to say that 334-yo tree isn’t on its own unique trajectory or that the sampling in any way represents the entire stem cell population of that particular tree, let alone the “idealized” telomere length changes over all members of the species over 3500 years? Dubious indeed.

But if we conclude from this study that extreme longevity in long-lived tree species doesn’t result in unopposed telomere elongation. Similarly, despite 8 years of telomerase activator ingestion daily, my telomeres maintain themselves in the newborn range, but not in the freakishly long lab mice range.

The preservation of a normal range of telomeres lengths instead of unopposed shortening OR lengthening is a sina qua non of negligible senescence in a mammalian model, in my opinion. With the telomere shortening that happens in the current human status quo, our healthy lifespan is usually curtailed to seven or eight decades.

Extreme elongation of telomeres would be a resource burden and a probably cause of loss of genetic integrity, like finding shoes for peop le with Guiness Book of World Records fingernails.

le with Guiness Book of World Records fingernails.

As an alternative immortality ‘hack’, we can’t afford to acquire a higher percentage of telomerase active stem cells like some immortal invertebrates, because then we would outgrow our cars and homes like a molting 140yo/19lb Lobster or a giant squid or jellyfish.

The fact that I haven’t grown taller, my body hair hasn’t grown longer, and no vestigial tails or other appendages have grown, accompanied by the fact that my telomere lengths are stable, is a very good thing because it means that the system is still maintaining itself in a sustainable manner.

(P.S. Please resist the urge to write to me about freakishly long telomeres in inbred and aging lab mice who lack the glutathione to fight oxidative damage and cancer. That just means that you have chosen to regurgitate a simplistic argument and will employ it to bark down all the rest of science and common sense like one of Napoleon’s dogs in Animal Farm).

1 thought on “5,000-year-old trees maintain their telomeres in a controlled range”

Pingback: Archives Week 5- May 1, 2022 – Recharge Biomedical